Reflections on My Higher Education Experience

Author: Vladyslav Hryhola | 16 August 2024

The longer I spent obtaining formal education, the more I realized the degree of corruption in the institutions I was attending. The result of this experience can be expressed as a lack of respect towards people affiliated with this education system. Now, let's see why.

My Expectations

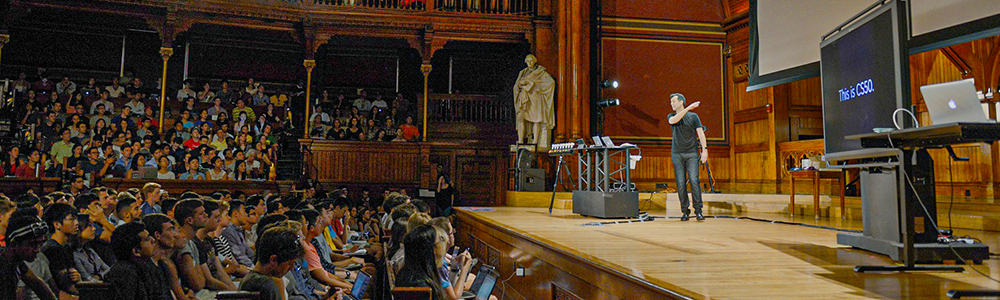

Before I went to college, I already had some idea of post-secondary education. My interest in programming started mostly with watching the CS50 course, taught by David J. Malan at Harvard University. This course established a certain standard of teaching, interaction with students, and a balance between exploring historical roots and showcasing new, relevant technologies. Today, I'd still recommend this course as a starting point for learning computer science. Another example of high-level lecturing is "Justice" by Michael J. Sandel, also from the good old Harvard University — a great introduction to moral and political philosophy.

Finishing school and preparing to go to college was thrilling to me. When I first stepped into the college's halls with their high Gothic ceilings, I saw a building that was once one of the first educational institutions of medieval Europe, originally a Jesuit monastery. However, now, I'm not convinced that the current state of the college is worthy of being housed in such a historical building. In my opinion, a low-ceilinged Soviet-brutalism building with no history would better correspond to the level of teaching at the college.

Lecturing

The first thing I noticed was that it was required to write down the lecture material in your notebook. And I don't mean that we wrote key notes, highlighted thoughts, axioms, or personal insights; I mean we wrote down the lecture itself, almost like stenography. Since the spoken lecture was much faster than the pace at which we could write, the lecturer had to significantly slow down the narrative, effectively turning the lecture into a dictation. Speaking slowly and forcing students to write means that they are not actually focused on the material being presented they are focused on trying to keep up with the writing speed in sync with the lecturer's speech.

But why? What's the point of writing down the lecture when it's obviously available as a PDF? Well, the answer is not that complicated — plausible deniability. What if there are questions directed at the college? What if an unexpected audit happens: "What on earth are you doing in there? Are you actually teaching like you're supposed to?" Of course, the college knows how to respond: "Of course we are! Just look at the students' notebooks! There's plenty of relevant information in there! Just look at how much we've taught them!" There's a saying, "fake it until you make it," except that last part isn't actually required, as I observed in college.

Teachers are not interested in teaching the course material. In fact, they seem more interested in avoiding it. When I studied discrete math, we skipped huge sections that explained important aspects of formal logic, such as quantifiers. Honestly, for someone like me, who loves formal languages and logic, this feels like a crime. If you know anything about formal logic, you know that it makes no sense to delve deeper into the subject without understanding the importance of quantifiers. I recall some reasoning behind why this section was skipped. The teacher might have had a tough experience with very hard, complicated exams on this topic and, wanting to do a good deed by not overloading the students, decided to omit it. But this, of course, is an overcompensation.

No to innovations

Teachers are not interested in innovations. At university, I was surprised to find that in the HTML coding course, instead of teaching modern tools, plugins, and layout-building methodologies, the teacher actually had us write code in the default Windows Notepad instead of an IDE, without any shortcuts or hints. You might try to defend this approach, saying it encourages learning the very basics of markup, tags, etc., but I strongly disagree. Learning the basics of HTML is not university-level knowledge, not even college-level — it could be covered in a high school course. At university, we should be learning something more advanced.

The same applies to college: we learned how to code in C++ by writing the code on paper, with a pen. Again, you might argue that this helps with understanding the fundamentals, but I disagree. You learn a formal language just like you learn a human language — by diving deep into the environment and practicing a lot. If you want to learn C++, you should practice in the real environment, in an IDE, repeatedly compiling your code, finding, and fixing your mistakes. That’s the right approach, not using a paper sheet and a pen.

And it extends beyond programming. When I heard that a teacher preferred Photoshop CS3 (released in 2007) over modern versions, I was shocked, but not entirely surprised. By that point, it had become something I almost expected.

Yes to conspiracy

But if not innovation or lecturing, what are teachers actually interested in? Conspiracy theories. And don't get me wrong — I find these interesting as well; I actually enjoy the fantasy genre. However, I'm not quite sure that a post-secondary education is the right place to share these ideas.

One of the teachers told us about an old essential Slavic word discovered by a "scientist," claiming it was the key and foundation of everything — the word "God" spelled out as a single symbol in a logo. I’m not sure what the source of this theory was, but it seemed like it might have come from someone with a fascination for fringe linguistic or historical theories, much like Alexander Khinevich.

Another teacher revealed the truth about Masonry and the "golden billion" theory. Ironically, this was probably the best and most dedicated lecturer I encountered, despite their interest in conspiracy theories.

Relics of the Soviet Union

If conspiracy theories sounds bad to you, I'll show you something not much worse - Marxism. Ukraine once was a part of Soviet Union. I spent some time in humanities groups online and already know that many disciplines have a Marxist influence, with a Marxist lens often used as a default perspective in various branches of the humanities. So, when I encountered this in philosophy classes, I knew what to expect and wasn’t surprised.

However, what I didn’t expect was to see Marxist traces in systems analysis course (should've been replaced with project management course in my opinion). There were numerous references to dialectical materialism (not to be confused with ancient Greek dialectics) as a default "methodology" for building theories. There were also references to the classics of dialectical materialism and communist public figures like Viktor Afanasyev (editor-in-chief of the journal Kommunist and deputy editor and editor-in-chief of Pravda), which are neither required for system analysis nor project management. And even if we are to use a philosophical foundation to establish basic methodologies in science (again, this is not required for project management course), it should not be this ambiguous leftist dialectical materialism but rather something close to postpositivism, which was advocated by Karl Popper, who rigorously criticized dialectical materialism.

How did we get here?

How did we get here? That’s a complex question. In my opinion, it’s due to the gradual degradation of the post-secondary education system in Ukraine. There’s a prevailing narrative in our society that a degree is essential. However, the truth is that not everyone needs one. Many people, who are not genuinely interested in science, philosophy, or other academic disciplines, still apply to universities because they feel they "have to." As a result, we end up with many individuals who are uninterested in education but are focused on obtaining a degree. The system then has to accommodate these individuals in some way.

In an ideal world, such people would either be denied admission or expelled later on. But we don't live in a perfect world, and corruption often turns these individuals into a source of revenue for bureaucrats. As one teacher explicitly stated: "The students who have potential and a desire to learn will learn anyway [despite the system's corruption]".

What a degree does not mean nowadays?

If I say that having a degree doesn’t necessarily mean that a person actually knows the subject of their field, it probably won’t be a big revelation. However, a degree might be viewed from a different perspective. Maybe it’s not just about actual knowledge; having a degree could also indicate that a person knows how to navigate a large, complex system, communicate with others, cooperate, and meet deadlines. This is one reason why a bachelor's degree is often a requirement in many job postings — to filter out individuals who may lack the stability to function effectively in large systems like universities or corporations.

I’m sorry to disappoint you, but this is also entirely true. I’ve personally seen deadlines missed by over a year, and this was not deemed sufficient reason to expel a student. In fact, if I were an employer choosing between two nearly identical candidates where one has a degree and the other does not but both have the same skills, I’d prefer the candidate without a degree. This person is more likely to think in unconventional ways and come up with innovative solutions — because they possess the same level of knowledge as the degree-holder but haven't spent time in inefficient or corrupt institutions just because they "had to."

How I learned what I've learned

The biggest takeaway from college that turned out to be truly useful was discovering the existence of various fields of knowledge and understanding what I should focus on. This led me to self-education. I read books on my smartphone during my commutes to and from college, which probably provided the most relevant information I received each day, despite spending most of my time at college. Much of my learning also came from video lectures on YouTube and other platforms. The internet is an endless source of knowledge if you know where to look. Combining this with extensive practice is how you really learn.